Roguerrants is a game engine for interrupted real-time 2.5D (parallaxed top-down) roguelike games, developed by Stéphane Rollandin, and is written in Squeak/Smalltalk. Stéphane announced on the Squeak developers list (here) the availability of Roguerrants on itch.io.

A “Roguelike” game is a sub-genre of RPGs, named after the classic 1980 game “Rogue.” It is defined by features such as dungeon crawling through procedurally generated levels, turn-based gameplay, grid-based movement, and the permanent death of the player character. Roguelikes have evolved over time, inspiring numerous variations and modern interpretations, often referred to as “roguelites,” which may incorporate elements like permanent upgrades or less punishing death mechanics.

The Weekly Squeak reached out to Stéphane Rollandin, who generously shared details about the development of Roguerrants.

What led you to use Squeak to develop a game? How is Roguerrants different from something you would have created using another programming language?

I have been working with Squeak for the last twenty years. I could just not work with anything else. I’ve been spoiled.

I first came to Squeak to port GeoMaestro, a system for musical composition based on geometrical structures that I made in the KeyKit MIDI environment. In KeyKit there are classes and I first met object-oriented programming there.

Someone from the csound-dev list I think told me Squeak would be a good fit for me, and this is the best piece of advice I have ever been given.

So I first used Squeak for music. GeoMaestro became muO, which is a huge system that eventually allowed me to compose my own pieces, although I have no musical education and no playing talent whatsoever.

In muO I did a lot of graphical stuff, and notably a family of interactive editors that evolved into the ones I use for Roguerrants maps and geometrical structures (navigation meshes for example).

muO taught me Morphic, which I believe is an incredibly underestimated pearl. It’s a beautiful framework. It’s amazing. I know a lot of people in the Squeak community (and even more in the Pharo one) think of it as a pile of cruft that needs to be reconsidered completely, but to me it’s just a wonderful framework.

Roguerrants is 100% a Morphic application. Without Morphic, I could not have done it at all. And without the tools I made for muO, I would not have considered building a system that ambitious.

Regarding graphics and sound, how do you implement these elements in Squeak? What advantages does the environment offer?

So, graphics are pure Morphic and BitBlt. I just tweaked a few things to make them faster, and made a few fixes. I had a hard time with composition of alpha channels, notably.

The advantages of Morphic is the natural division of tasks, where each morph draws itself. Graphics are naturally structured; more about this below.

Sound is also supported natively in Squeak. In muO I did mostly MIDI, and some Csound, but also a little audio synthesis so I known the sound framework quite well. I fixed a couple bugs there too. And I made editors for sound waves and spectra.

In Roguerrants, each monster class uses its own synthesizer and actually plays musical notes. Its utterances are composed with muO. I can generate adaptive music, although this is still in an early stage.

The concept of free motion and an organic grid is intriguing. What motivated you to incorporate these elements in Roguerrants, and did you encounter any challenges during their implementation?

I like things to be free from grids, in general. But grids are useful, so the main point is to be able to treat them as a game component just like another instead of having them being the paradigm everything happens within.

In Roguerrants everything happens in real-time and is located via the plain morphic coordinates system. That’s the base. The grid comes second. The turn-based structuration of time also comes second. In fact, the whole of Roguerrants comes second to Morphic itself. The game playground is just a single morph. The time evolution is the Morphic stepping system, no more, no less.

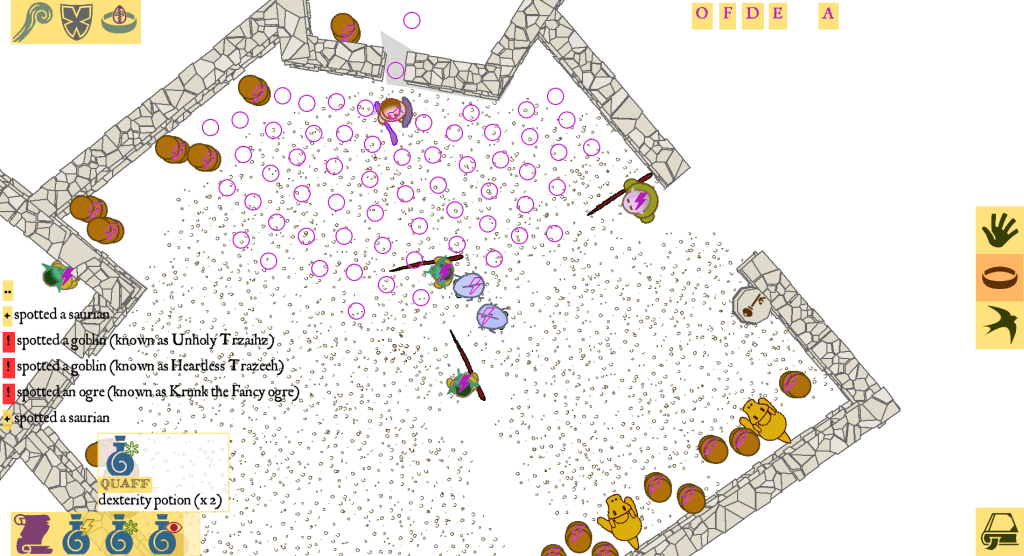

Organic grids are relaxed Voronoi tesselations that take into account the surrounding of the controlled character. The challenge there is make them seem natural to the player.

For example, the grid should not feature cells at places the player do not see (because it may give the player hints about what’s there) but this is a subtle issue, because some of these places have been seen recently, so why no allow access?

There are also different ways the grid adapts to what the player does.

For example, not all cells in the grid are reached at the same speed. If the player makes a small move, it will also be a slow move. This is to prevent the player from abusing the turn-based system by being too cautious. On the other hand, a long move is faster: the player is running. This makes sense if you remember that once the move is chosen, it cannot be interrupted; if a source of danger is encountered during a move, too bad.

How does the grid adapt to that? Well, the base navigation grid is generated within a specific radius around the player. If the player runs close to its border, the grid for the next turn will have a smaller radius: the player will not be able to run twice in a row. One turn is needed for resting somehow. This creates a nice ebb and flow in dangerous situations.

Another example: when the player character is stunned, its navigation grid has larger cells. The stunned condition has several effects, and one of them is to make the player more clumsy in the way it moves.

So a lot can go on when one thinks of what it means to be provided a navigation grid generated differently for each turn. I am still exploring what can be done there, and as I said the challenge is to make all the mechanics invisible to the player, yet there in an intuitively meaningful way.

Generating graphics without a tile-based system is a unique challenge. How did you tackle this issue in Roguerrants?

Let’s see this from the point of view of Morphic, again. A morph can have any shape and size. You just put it on the World, and that’s it. It can draw itself, so it handles its own part of the overall display.

So in that sense it is not a challenge at all, just the morphic way.

Now there is a little more to it.

As I said above, the game playground is a morph (a subclass of PasteUpMorph, the class of the World). It has a very specific way to draw itself, unique in the world of morphs. For one thing it draws it submorphs layers by layers, allowing the 2.5D parallaxed display, and also it allows any of its submorphs to paint anywhere.

So in addition to drawing itself, a morph in Roguerrants can decorate part of all of the game world in its own way. That’s how the ground is displayed for example.

High-level components like activities and missions can significantly affect gameplay. How do these elements drive character behavior in Roguerrants, and what distinguishes your approach?

This is one of the most involved technical points.

First there is ModularAgency. This is a design for giving any object an arbitrary complexity, in a dynamic way. I do not have the room to discuss this further here, but there is a lot to say; it is the core design of Roguerrants, and definitely one of the things I am the most proud of. It is a kind of ECS (entity component system), but a very unique one.

Via its #agency, a SpriteWithAgency (the subclass of Morph that all game actors are #kindOf:) has a dynamic library of components, each attributed a specific responsibility. There is really a lot of them. At the time of writing, there are 165 implementors of #nominalResponsibility, which means there is that number of different, well identified, aspects of the game that have a dedicated component. A NPC has around 25 to 30 components.

Among them are the ones responsible for its #activity and #mission.

The #activity component directly drives the #deepLoop component, which is the one that handles the #step method of a Sprite.

For example, if the #activity of a goblin is a journey, it will ultimately add to the goblin #deepLoop, at each morphic step, a command for changing its position and its orientation.

Now this is just the end point of a complex computation, because to do so it needs to know where to go, and so it consults the goblin #destination component, it asks the game #cartographer to produce a navigation mesh and do some A* magic there [ed. A* is popular algorithm used to find the shortest path from a starting point to a goal point on a graph or grid], it asks its #collisionEngine if there is any obstacle in the way, and if there is one that hinders the journey it delegates the problem to the #journeyMonitor component. You get the idea.

But the journey may need to be interrupted, or even discarded entirely. An activity is a moment-by-moment thing, it does not have a broad scope in terms of the overall behavior of the agent.

When an activity signals that its job is done, the #mission component gives the agent another activity. It is the #mission that implements what the agent behavior is about. Two agents can have a similar activity, like going from point A to point B, but very different missions: one can be heading to a chest to fetch something, while the other one is actively hunting the hero. Their activities at a given time are what their respective missions told them to do; they will be given very different activities after they arrive at their destinations.

When a mission is accomplished, the #mission component removes itself, and in the process it installs a specific kind of activity, an idle activity. The idle activity gives the agent a new mission.

So there is an interplay between mission and activities. Both components taken together make an agent do something in a well-defined context.

Then there are quests. Quests are components that give an agent a set of goals. They push the narrative forward. They can give missions. At the level of quests, we deal with the “why?” of an actor behavior. That’s the level of the story, of the game scenario.

Implementing original systems often comes with its own set of difficulties. What challenges did you face while creating your geometry- based combat and magic systems, alongside a high-level architecture for actor behaviors?

It’s not exactly a challenge, but computational geometry is tricky and it takes some time to get it right. Roguerrants uses convex polygons a lot, so I had to implement all related algorithms. The most complex one was Fortune’s algorithm for Voronoi partition. It took a lot of revisiting to make it stable and understand its domain of usability.

So why polygons?

In roguelikes, combat happens upon collision: you move your character towards a monster, there is an exchange of damage according to your stats and the monster stats, and life points are lost.

Collisions in a grid system is based on the grid connectivity: you collide with neighbor grid cells.

When moving freely, with an arbitrary shape, collision is more a geometry test: are polygons intersecting? So at this point, it made sense to me to have weapons, armor and hurt boxes also collide, individually.

When a character yields a sword, that sword attaches an impacter to the agent. The impacter is a polygon convering the area where the sword deals damage.

A creature has one or more hurt boxes (also polygons). If a weapon impacter overlaps one of these boxes, damage is dealt. And then, the impacter enters a cooldown period during which it becomes inactive. Armor works similarly.

The magic system uses geometry in another way.

Let’s take for example the Ring of Blinking. When equipped, the player character can teleport itself to a nearby location. What are its choices? It could be a grid, like the one used for navigation. But blinking is a powerful ability, so it’s better to give it some limits, and even make it dangerous – that’s much more fun. We can do that with geometry.

The places the player can blink into are a set of polygonal areas arranged in a mandala. When the blinking ability is not in cooldown, these places are small. Each time blinking is used, they grow. As time passes, they tend to get smaller again. If the player blinks too often, its mandala will feature very large regions. Blinking into a region only guarantees that you will land inside, not where. And so the more often you blink, the more you risk to teleport at a bad place, possibly even inside a wall or a rock (and then you die horribly).

Different abilities have different mandalas and different uses of their polygons. The exact mandala you get also depends on where you are, because magic is also a negociation between an actor and its surroundings. Some places forbid, enhance or degrade magic. This dimension of the game will be expanded a lot in the future, because it informs its tactical aspects.

The inclusion of biomes as first-class objects is a compelling design choice. How does this decision enhance the logic and functionality of your game?

This is a natural consequence of the way spatial partition is implemented.

Game maps in Roguerrants can be limited, or unlimited. Even when limited, they may be large. For this reason, they usually are not completely spawned. Parts of a map are suspended, waiting to be populated and made alive when the player, or another important actor of the game, approaches them. When they are not useful anymore, they get suspended again.

This means maps are modular. There is usually a top tesselation of large convex polygons, which may be hexagonal. Often each polygon is itself subdivided in regions, and this goes on down to the desired granularity.

At each region or subregion is associated a modular agency, called a local power. Local powers have many components, notably the component responsible for spawning and despawing game objects living in the corresponding region.

Local powers are very important. They are actors, invisible to the player, that inform a lot of what happen in the game, anything actually that is related to location. It is dark there? Who lives there? What is the nature of this place? Etc.

And so it makes sense that for a biome to be a component of a local power. Imagine a forest surrounded by fields, a forest that get denser at its core. Let’s say the whole map is an hexagonal tesselation. We give a biome to the hexagonal cells for fields, and another biome for the forest cells, plus yet another biome, probably a child of the former one, for the forest core. We then ask each cell to generate trees – that’s one line of code. The component(s) responsible for spawning trees is looked-up via the biomes. Fields will not generate trees, forest cells will generate them, and dense forest cells will generate a lot of them. Rocks will be different in fields and forest, etc. The different creatures that appears in the game will also be looked up via the biomes – snakes in the fields, giant spiders in the core forest, etc.

How did your design philosophy for Roguerrants shape the features you chose to implement in the game?

The design philosophy can be summarized in a few principles:

- Each notion, each concept, each dimension identified as orthogonal to the others in the game design must be reified into an object (often a component) responsible for its implementation

- It should always be possible to go deeper in said implementation.

- It is nice to preserve the variety of ways it can be implemented.

For example, collision. What objects in the environment should we consider as potential obstacles? How do we test for actual collision?

The answer is to not look for The One Way To Collide, but instead to provide the tools (including the conceptual ones) allowing to express the problem effectively, and then use them to build the different answers adapted to different contexts.

So for example, a large group of gnomes, of an army of goblins, will bypass a lot of collision tests, so that they do not lock themselves into some ugly traffic jam. They will interpenetrate a bit.

A projectile, which is fast and small, will not test its collision in the same way as a big and slow monster. The projectile will consider itself as sweeping along a line and look at the intersection of that line with surrounding objects. The monster will look for the intersection of unswept polygons. Also the projectile has a target, of which it is aware, so it will take special care of it.

When riding a monster, a goblin will delegate the collision responsibility to the monster. No need to do anything, it’s just the rider.

A character moving along a path computed from a navigation mesh do not need to test for collision against walls – the mesh already took them into account.

But a character driven in real-time, via the mouse, by the player, do need to consider walls. It has a different #collisionEngine component.

Now if this mouse-driven character is blocked, lets says when attempting to move between two trees, it is maybe because the path is narrow and the player did not find it (sometimes this is a matter of pixels). At this point the collision engine interacts with the #cartographer (the component responsible for computing navigation meshes) and checks if indeed a path exists. If it does, it follows that path and succeeds in moving between the trees. The player did not notice anything. Computer-assisted driving! That’s point 2 above: it is always possible to go deeper in the implementation.

So when implementing a new feature, the first task is to express what I want to do in terms of the notions already reified in the game engine. If a new notion is introduced by the new feature, I create the corresponding components, maybe refactoring and refining the existing ones.

Then I come up with a lousy implementation of the feature, and live with it for a while. When I’m fed up with the ways it does not work well, I go deeper, I do it better. I am constantly revisiting existing features and the way all components interact together, which is only possible because refactoring in Smalltalk is so painless and easy.

Looking ahead, what enhancements or new features do you envision for Roguerrants?

First of all, I want to expose all the features that are already there. That’s why I released two projects on itch.io:

One is Roguerrants, the game engine.

The other one is a game. It is called, tongue in cheek, The Tavern of Adventures, and at the moment it is very primitive. I intend to grow it into something fun that will illustrate a lot of systems that are hidden in the engine at the moment. For example, you can fly. You can also control a party. You can play board games. There are rivers and lakes, lava pools, bottomless pits, basilics, dolmen, villages… You can trade and exchange intel with NPCs. You can have procedurally generated, evolving scenarios. Victory conditions that are not known in advance.

Then, for the future, I can see two main features coming for the game engine.

One is adaptive music. I would like the game to generate its own music. This is a long-term goal, and where I will go back full muO.

The second is a declarative API. A very simple format, even usable by non-programmers, to create custom games. I have already begun this, and the little I implemented already gives me a huge boost in the speed of game contents generation.

Player experience is a crucial aspect of game design. What do you hope players take away from Roguerrants, and how do you see their experience evolving as you continue to develop the game?

Well at the moment I do not have a game for them. I only have a game engine. I first need to upgrade Tavern of Adventures to a proper gaming experience, with tactical situations, exploration, meaningful decisions and a bit of strategizing. We’ll see how it goes.

Try It Out!

If you are interested in exploring the capabilities of Roguerrants and experimenting with its features, you can find more information about the project on its official itch.io page here. Stéphane also mentioned The Tavern of Adventures, which can be found here. Additionally, do not forget to check out the muO project (here), which focuses on musical objects for Squeak, offering a unique dimension to your creative explorations. We encourage you to dive into these exciting projects and do not miss the opportunity to explore the innovative possibilities they offer!

Have a great time with Smalltalk and keep on Squeaking!

Leave a comment