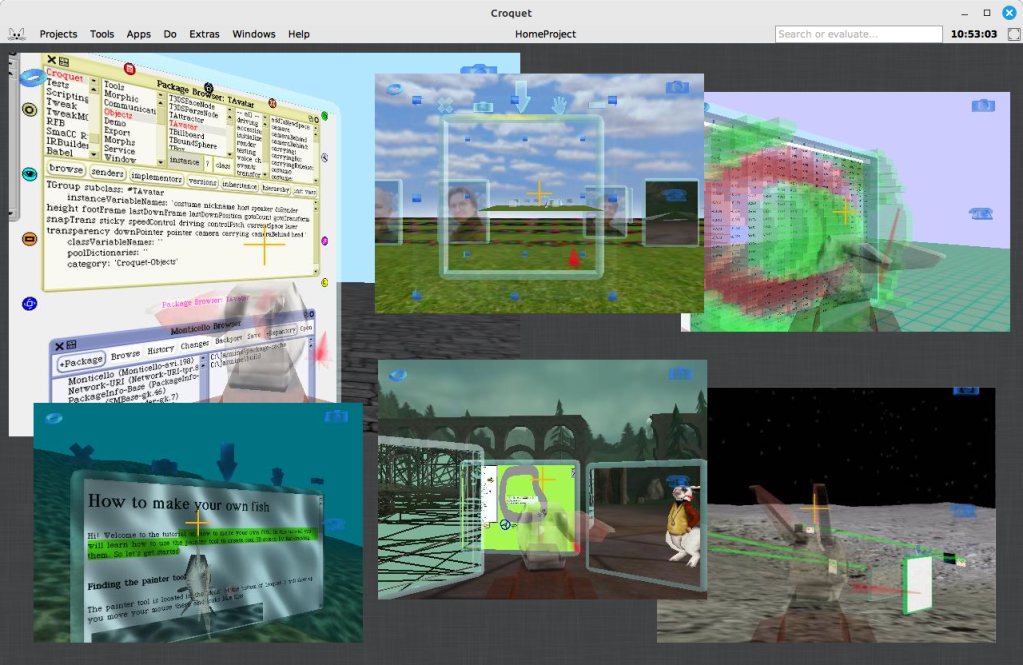

An initiative has recently emerged within the Squeak community to explore bringing Croquet into the modern Squeak 6.0 environment, with their efforts opening up possibilities for personal and educational applications, and potentially paving the way for long-term developments. Community members Edwin Ancaer and Timothy have taken it upon themselves to explore, port, and troubleshoot Croquet – an ambitious collaborative 3D environment originally designed to run in earlier 32-bit versions of Squeak.

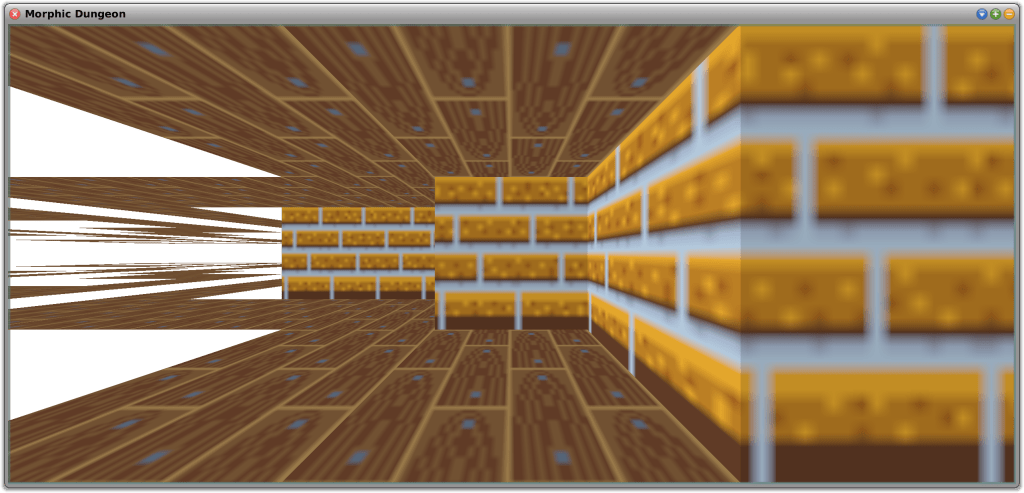

Croquet was a groundbreaking software architecture designed for deep collaboration, originally built as an open, free, and highly portable extension of the Squeak programming system. It provided a platform for both development and real-time collaborative work, with no separation between user and developer environments. Focused on 3D shared spaces, Croquet enabled users to interact in context-based collaborations, observing each other’s actions and focus in real time. A collaboration protocol called TeaTime powered this synchronization, and rendering was based on OpenGL. While newer, proprietary descendants of Croquet have evolved since, the version being revived in Squeak 6.0 reflects this original, exploratory vision.

Croquet Jasmine, a developer’s release of the system, is available and can be run live in a web browser using the SqueakJS virtual machine – allowing others to easily explore Croquet without a local setup. You can try a live version here: codefrau.github.io/jasmine/.

Technical Hurdles and Graphics Considerations

Efforts began early in the process, building on Nikolay Suslov’s work to get the original Open Croquet running on the latest versions of Squeak 5.x. His work laid the groundwork for achieving compatibility with Squeak 6.0. You can explore his repository here: github.com/NikolaySuslov/croquet-squeak. You can also check out detailed steps Nikolay has provided to bring Croquet into an early alpha version of Squeak 6.0 here.

A primary obstacle encountered was the tight coupling between Croquet and OpenGL 1. As Vanessa Freudenberg pointed out, OpenGL has been deprecated on macOS for years, complicating efforts to run the system on 64-bit machines. Vanessa suggested considering Vulkan or OpenGL 4 as possible alternatives for the rendering backend.

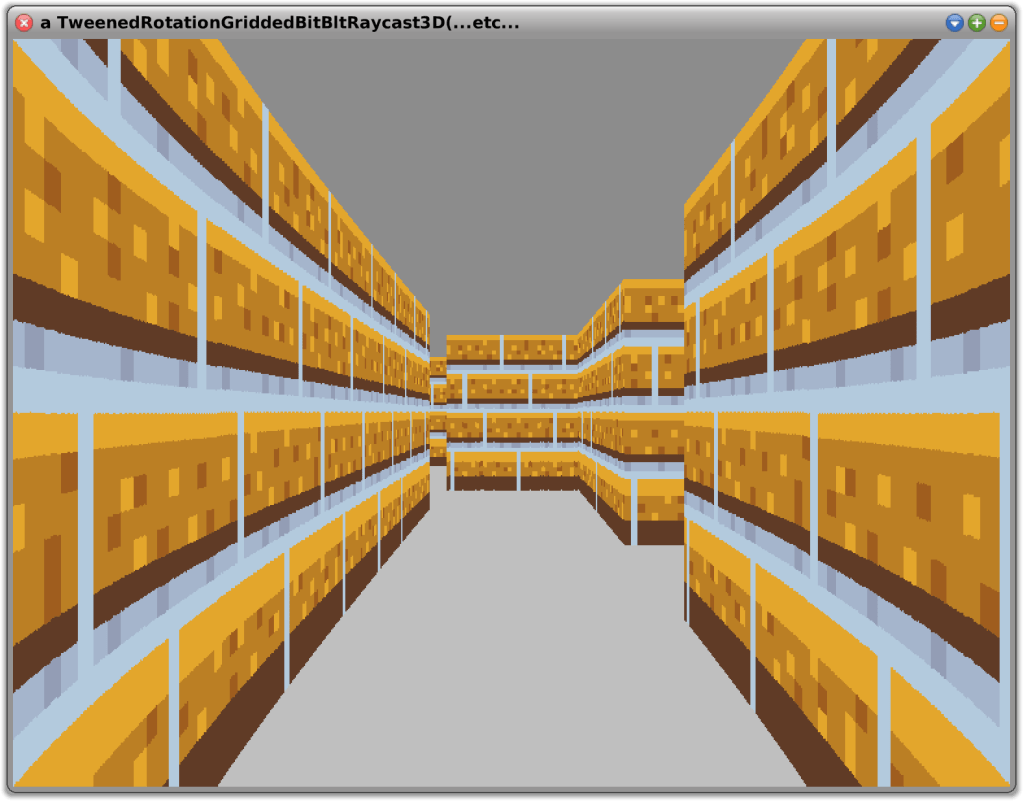

In consideration of a long-term solution, it is helpful to explore the potential paths forward, each with its own trade-offs:

- Re-implement OpenGL 1 as a compatibility layer – Offers limited long-term value and would still not work effectively on macOS due to deprecated OpenGL support and the absence of modern graphics capabilities. Efforts like MoltenGL, which aim to bridge OpenGL to Metal, do not support OpenGL 1, making this path particularly challenging.

- Migrate to a modern OpenGL (3.x or 4.x) – More viable than OpenGL 1 in terms of features, and partially supported on macOS (up to OpenGL 4.1). However, it is deprecated and no longer maintained on Apple platforms, making it an unstable foundation for future development.

- Adopt Vulkan for high performance – A modern, low-overhead graphics API designed as a successor to OpenGL. While Vulkan is not natively supported on macOS, it can be used via MoltenVK, which translates Vulkan calls to Metal. This option requires significant integration work but offers the most long-term potential across platforms.

For a long-term solution, Vulkan appears to be the most promising path – essentially a modern, cross-platform successor to OpenGL, developed to overcome many of its limitations. Although not natively supported on Apple platforms, Vulkan’s compatibility through MoltenVK makes it a viable candidate for achieving performance and portability across environments.

While these options are worth exploring for long-term solutions, they may be unnecessarily complex for personal or educational use. However, the current efforts could prove valuable down the road by revealing key details, helping future work begin from well-understood points in the development process.

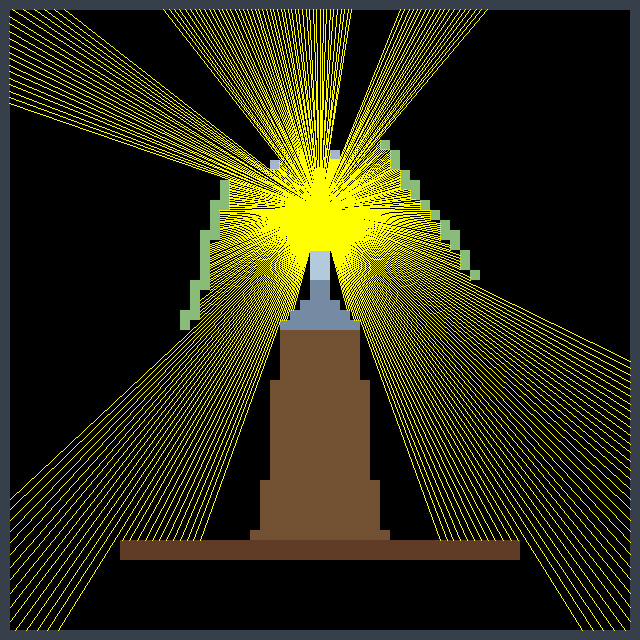

Vanessa has managed to run Croquet Jasmine without modifying the Smalltalk code by using the browser-based SqueakJS VM, with a custom OpenGL 1 implementation written in JavaScript. This was accessed via FFI and mapped to modern WebGL. The approach preserves the original graphics code inside the image while offloading rendering to the browser, and could serve as a model for similar efforts going forward.

Debugging and the Role of C in a Self-Hosting Environment

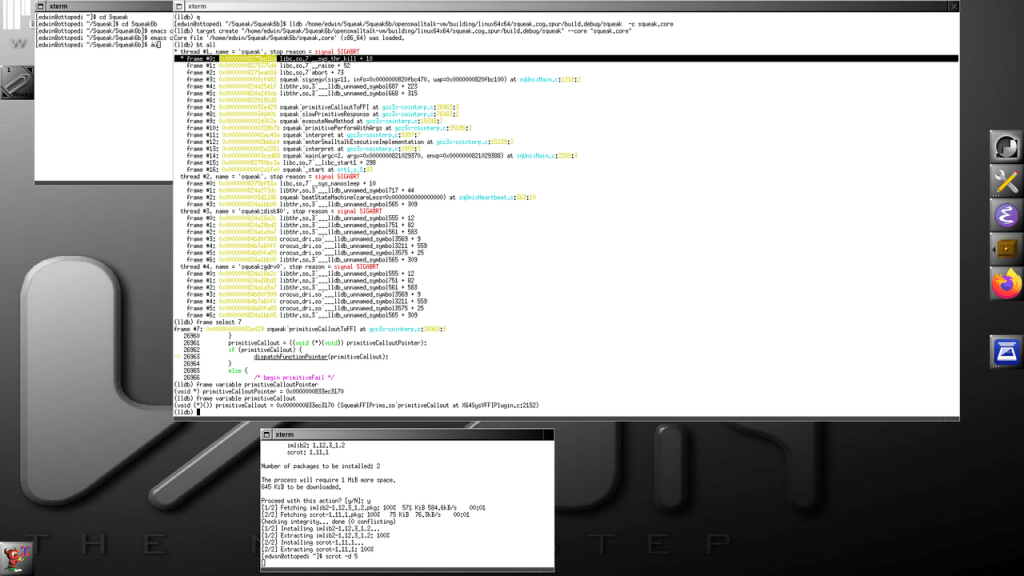

In efforts to get Croquet working with Squeak 6.0, contributors encountered challenges requiring low-level debugging. Their focus shifted to analyzing behavior via the debug VM, aiming to isolate root causes of instability or failure.

One may wonder why Squeak, being a self-hosting environment, might still require work in C. The environment is written in Smalltalk and is capable of building and evolving itself entirely from within. This self-hosting capability enables fast iteration, deep system visibility, and live modification of running code – all without leaving the environment.

However, Squeak runs on a virtual machine, with performance-critical parts written in a restricted subset of Smalltalk known as Slang (Swiki link). Slang is not a separate language, but a subset of Smalltalk designed to be translatable into C for compilation. This allows the virtual machine, which is largely written in Smalltalk, to be compiled into efficient native code for multiple platforms. When issues arise at the VM level – such as those involving primitives, foreign function interfaces, or memory management – developers must drop down into the generated C code to diagnose and resolve them. You can read more about the Squeak VM on the Swiki here and here.

The benefit of this design is excellent portability: the Smalltalk environment remains consistent across platforms, while only the VM layer needs to be recompiled or adapted for different operating systems or hardware. Having this level of separation allows the Squeak image to remain consistent across multiple platforms without exposing the underlying hardware implementation to the image code itself.

Further analysis suggested that inconsistencies between expected and actual behavior in the virtual machine’s handling of system-level function calls were at the heart of the issue – at least for now. By carefully tracing how external interfaces were being resolved and invoked, the contributors were able to isolate a likely point of failure. The realization was met with enthusiasm, signaling meaningful progress toward resolving the issue.

The Irony of Debugging and Systems Development

Edwin humorously remarked that he never expected working in Smalltalk would lead him back to debugging C code – a twist that underscores the unpredictable nature of systems development. Tim Rowledge added that, during his time at ParcPlace, it was an inside joke that those who got hooked on Smalltalk inevitably ended up spending too much time writing C, while the C++ fans who joined the team found themselves writing Smalltalk instead. The irony of this unexpected reality highlights the surprising paths developers take when working with complex systems.

Looking Ahead

We extend deep appreciation to Nikolay Suslov for his foundational work in bringing the original Open Croquet to Squeak 5.x, which has served as a solid base for moving toward compatibility with Squeak 6.0. A special thanks also goes to Edwin and Timothy for their time, dedication, and resourcefulness in troubleshooting and adapting Croquet to modern Squeak 6.0 systems. Their efforts contribute to the broader community by preserving an important piece of Squeak history and helping to lay the groundwork for future advancements.

The effort to bring Croquet to Squeak 6.0 is ongoing. We wish those involved continued success and invite anyone curious to jump in, contribute, and join the effort to keep Squeak a vibrant environment for innovation and exploration!

Have a great time with Smalltalk and keep on Squeaking!